My Sorolla: From the Pyrenees to the Pacific

Reprinted with permission from Fine Art Connoisseur

September/October 2014

Editor’s Preface: Learning from Sorolla

By Peter Trippi

The gifted Spanish painter Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863-1923) continues to win admirers and inspire other artists long after his death.

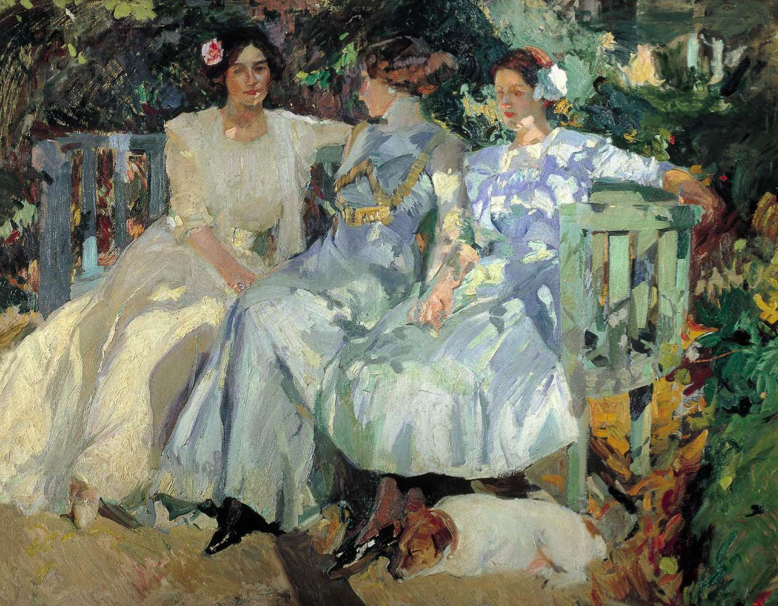

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863-1923)

My Wife and Daughters in the Garden

1910, Oil on canvas, 65 3/8 x 81 1/4 in. Colección Masaveu, Oviedo, Spain

Premiered last December at Dallas’s Meadows Museum of Art, the important touring exhibition Sorolla and America was curated by the artist’s great-granddaughter, Blanca Pons-Sorolla, to survey his achievements and highlight his brilliant success on these shores. It features more than 150 paintings and drawings, loaned by museums and private owners in the U.S., Spain, and Mexico.

Having just concluded its popular summertime showing at the San Diego Museum of Art, the exhibition is now set to grace Madrid’s Fundación MAPFre (September 23, 2014-January 11, 2015), where it will be enjoyed by guests traveling on the Iberian Art Cruise organized by Fine Art Connoisseur.

Rather than repeating what the curatorial team has stated so compellingly in its magnificently illustrated catalogue, we decided to shine light here on how talented American artists have been using this year’s encounters with Sorolla to move the field forward.

Peter Trippi is editor-in-chief of Fine Art Connoisseur.

My Sorolla: From the Pyrenees to the Pacific

By Timothy J. Clark

Timothy J. Clark (b. 1951)

The Jota in Huesca

2014, Watercolor on paper, 20 1/2 x 14 1/2 in. Lois Wagner Fine Arts, New York City

While planning a trip to northern Spain earlier this year, I revisited New York City’s Hispanic Society of America to study Sorolla’s monumental, 14-panel Vision of Spain cycle. I was especially eager to examine the scene showing costumed Jota dancers from the northeastern province of Aragon.

In May, I spent three weeks traveling along the spine of the Pyrenees, from their base at the Mediterranean, through Northern Aragon, and onward to their Western margin near the Atlantic. I stopped to paint in the village of Anso for several days. More than 30 years earlier, I had driven in circles around this and several other remote Pyrenean hamlets, whose residents still speak a unique dialect incomprehensible to speakers of Spanish like me.

During both visits, my objective was to witness the region’s characteristic dance, the Jota. The traditional clothing in which it is performed was actually worn by some residents daily well into the 1990s, when even this remote region began to adopt garments designed and manufactured elsewhere. Yet Anso remains difficult to reach, which is surely for the best.

Before leaving Spain this May, I made another visit to Madrid’s Museo Sorolla, the elegant villa where the master lived and worked. There I was delighted to see an exhibition of Spanish costumes and photographs he had used as references, including several related to Jota dancers.

Only a few weeks later, I was at home in Southern California finishing several of my new Pyrenean paintings, and also visiting the Sorolla exhibition at the San Diego Museum of Art. There I was pleased to see artworks ranging in scale from intimate to wall-size. The renowned masterworks were thrilling, of course, yet working artists and scholars can actually learn more from Sorolla’s field studies, his commissioned portraits, and even a few of the (often unsigned) works that other viewers might consider unsuccessful.

These “other” works demonstrate Sorolla’s genius. For example, his renowned depiction of Louis Comfort Tiffany in a garden moved the standard parlor portrait into modernity. The freedom of his field studies is progressive and abstract; they inspire me not because they were made outdoors, but because of their interpretation of color, strong design, and free use of paint. What a treat to revel in Sorolla’s ease of execution, and to see where he stumbled when the subject did not interest him.

Timothy J. Clark (b. 1951)

Baroque Altar, Aragon

2014, Watercolor and shell gold on paper, 20 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. Harmon-Meek Gallery, Naples, Florida

I’m often asked why Sorolla is not better known today. Sorolla and America confirmed that he enjoyed a successful career, yet now his fame is a fraction of that of Picasso, another Spaniard who was 18 years younger and a world apart aesthetically. It seems to me that Picasso’s main contribution, Cubism, was copied by others and so became a dominant style, while the skill set needed to paint in Sorolla’s mode requires gifts far beyond understanding a specific stylistic “language.”

Many artists have tried, and still try, to paint like Sorolla. Alas, it’s hard to lead a movement when you’re the only one who can master the necessary moves. Weak followers damage your “cause,” which is exactly what happened in the 1910s and 1920s as Sorolla aged, and as opinion leaders turned their attention from virtuosic skill toward ideas as art (e.g., Cubism, Dada, Surrealism). Especially after the horrors of World War I, Sorolla’s celebration of beauty appeared out of sync with the times.

After seeing Sorolla and America, it slowly dawned on me that — without planning to — I had just painted in the same remote Pyrenean village that Sorolla visited. There he surely appreciated, as I did, not only the abundant sunshine, but also the shadows (both physical and psychological), exploring them in a subtle, almost metaphysical, language of his own. The exhibition further increased my respect by demonstrating how strongly Sorolla was influenced by earlier Spanish masters, even as he incorporated modern advantages: photography, field sketches, the latest paints and materials, travel by steamship to complete his American commissions, and the relocation of windows in his Madrid studio to get the light exactly right.

On May 31, I was fortunate to attend the San Diego Museum symposium focused on its concurrent exhibitions of Sorolla and of Robert Henri’s Spanish subjects. It featured talks by director Roxana Velásquez, curator Michael Brown, and professor Elizabeth Boone, but I especially enjoyed the talk by Hispanic Society curator Marcus Burke, who brilliantly set Sorolla’s achievements into their rich art-historical contexts. Later I was very glad to welcome Dr. Burke and Dr. Brown to my studio to see the Spanish scenes I had just created.

This has truly been my Sorolla year, and I applaud the San Diego Museum of Art for presenting his artistry so well.